by François LEBAS

Directeur de Recherches honoraire de l'INRA

English revised version of "Biologie du lapin" , translated from French by Cathy R. Martin and Joan M. Rosell

Edition 2020

|

Biology

of the Rabbit

by François LEBAS Directeur de Recherches honoraire de l'INRA English revised version of "Biologie du lapin" , translated from French by Cathy R. Martin and Joan M. Rosell Edition 2020 |

|

| 4.1 Some anatomy reminders : situation in adult | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The alimentary canal of an adult (4-4.5 kg) or subadult (2.5-3 kg) rabbit is about 4.5 to 5 metres long. Its position in the abdominal cavity is shown in figure 10. The digestive segments and their main characteristics are described in figure 11 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mouth | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| As previously indicated (chaper 3), the teeth grow continuously and their masticatory function is moderate. The salivary glands (parotid, maxillary, sublingual and zygomatic or orbital) produce saliva containing very little amylase (25 µmol of maltose obtained from the starch per mg of salivary protein, compared to 250 or 450 for the pancreatic juice). The amylase content is independent of the starch content of the feed ration or whether the animal has eaten or not (Blas et al., 1988). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Esophagus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The oesophagus is between the trachea and the spinal column. It allows the alimentary bolus to move from the mouth towards the stomach only. Regurgitation never occurs, even by accident | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stomach | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Small intestine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The small intestine which follows the pylorus, measures about 3 m in length with a diameter of about 0.8 to 1 centimeter. It is conventionally divided into duodenum, jejunum and ileum, the terminal part. The bile duct which brings bile from the liver, opens at the beginning of the duodenum, immediately after the pylorus. Its opening into the duodenum is regulated by the sphincter of Oddi. Remember that in rabbits bile is secreted almost continuously by the liver, then stored in the gallbladder before it is evacuated in the duedenum. The pancreatic duct (also known as Santorini duct) opens towards the end of the duodenum about 40 cm from the pylorus. On the wall of small intestine, plaques of lymphoid tissue about 1 to 2 cm in diameter are observed in place. These are Peyer's patches. The multiple glands present in the wall of the small intestine secrete numerous enzymes which complement those secreted by the pancreas. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The content of the small intestine is liquid, especially in the first part and completely empty segments of approximately 10 centimetres are quite normal. The pH, which is slightly alkaline in the first part (pH 7.2-7.5), becomes progressively more acid until it reaches 6.2 - 6.5 at the end of the ileum. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Caecum | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The small intestine ends at the base of the caecum via the sacculus rotondus, which contains the ileocaecal valve.The wall of the later is formed by lymphoid tissue.The caecum forms a second reservoir ( the first is the stomach) and is 40-45 cm in length, with a mean diameter of 3 to 4 centimetres. It contains 100 - 120 g of a homogenous paste, with a mean of 22 % dry matter (DM) and a pH close to 6 (figure 13). The caecal wall is invaginated in the form of a spiral with 22-25 coils, thus increasing the mucosal surface area in contact with the caecal content. The caecal appendix (10-12 cm) is situated at the distal end of the caecum and has a clearly smaller diameter. Its wall is formed by lymphoid tissue. Very close to the end of the small intestine or the "entrance" to the caecum, is the beginning of the colon, also known as the "exit" . The caecum thus resembles a no exit diverticulum, on the axis small intestine - colon (figure 11 above). Physiological studies show that this diverticulum-reservoir is a place of obliged transit; the contents circulate from the base to the tip, passing through the centre of the caecum and returning to the base, along the wall. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Colon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| After the cecum, is the colon of about 1.5 m. It is first characterized by the presence of haustra (small pocket-shaped bulges) over about 50 cm: this is the proximal colon. After a short section of about 1 to 1.5 cm carrying the only striated muscles of the digestive tract and called fusus coli, the wall becomes smooth in its terminal part; this part is called the distal colon. Its last part is called the rectum and ends at the anus. The latter carries the anal glands. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The digestive tract is relatively more developed in young rabbits than in adults. It reaches its definitive size when the rabbit weighs 2.5-2.7 kg, a weight which is only 60-70 % of its adult weight. Two vital organs release their secretions into the small intestine: the liver and the pancreas. Hepatic bile contains salts and various organic substances, but no enzymes. It indirectly aids digestion. In contrast, the pancreatic juice contains a considerable amount of digestive enzymes which permit protein (trypsin, chymotrypsin), starch (amylase) and fat (lipase) degradation. In addition to their digestive functions, liver and pancreas have very important functions in relation with rabbit's general metabolism | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Conclusion on the anatomy of the digestive tract | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4.2 Digestive development according to age and physiological status. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4.3 Physiology of digestion and caecotrophy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Digestive transit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

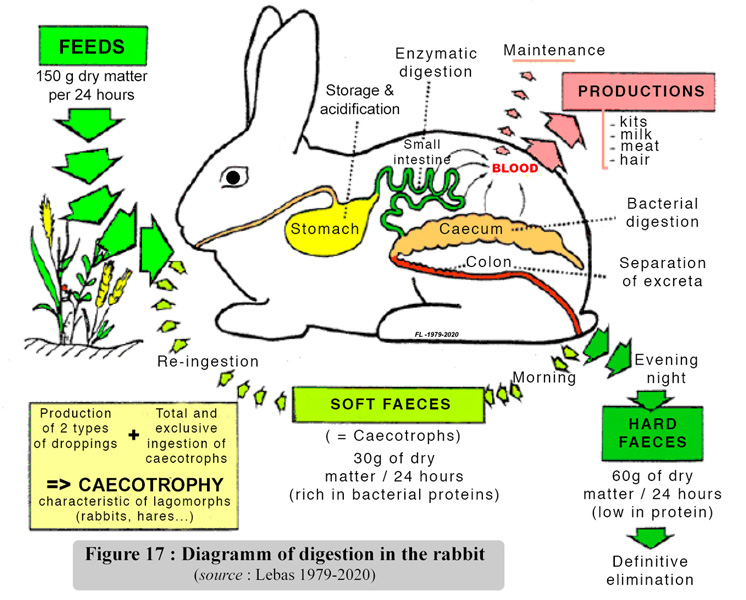

| Consumed feed particles swiftly reach the stomach where they find a very acid medium and remain there for a few hours (about 2-4) without undergoing very significant chemical changes. Marked acidification occurs, which causes various substances to solubilise and beginns protein hydrolysis as a result of the action of the pepsin. The stomach content is progressively «injected» into the small intestine in the form of small waves caused by strong stomach contractions. From the moment it enters the small intestine, the content is diluted by the bile flow, the first intestinal secretions and, finally, by the action of the pancreatic juices. Enzymes contained in these secretions enable the release of easily absorbable elements which penetrate the intestinal wall and are transported to the cells via the blood. After remaining in the small intestine for about 1.5 h, the particles that have not been degraded enter the caecum where they remain for some time (2-12 h), during which they are attacked by the bacterial enzymes in the caecum. The elements issued of the degradation by this new method of attack (mostly volatile fatty acids) are released. They then penetrate the digestive tract wall and are absorbed into the blood. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The content of the cecum in turn is evacuated to the colon. Approximately half of the content is coarse and fine feed particles that were not previously degraded. The other half is bacterial bodies that have developed in the caecum at the expense of the elements coming from the small intestine, as well as the remains of digestive secretions also from the small intestine. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The alternative functioning of the proximal colon: basis of the duality of excretion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Tiil this point , the function of the digestive tract of the rabbit is no different from other monogastrics. However, the dual nature of the functions of the proximal colon is unique. If the content enter the colon early in the morning, it undergoes few biochemical transformations. The colic wall secretes a mucous which progressively envelopes the pellets formed by the contractions of the large intestine wall. These pellets form an elongated cluster, called soft faeces or "caecotrophs". It is a different matter if the caecal content passes into the colon at another time during the day. In this case, the colon contracts in alternating directions; some of these contractions tend to empty the contents "normally" and others send it back towards the caecum. Due to the differences in the power and speed of movement of these contractions, the content is squeezed out like a sponge. Most of the liquid fraction, which contains soluble products and the fine particles (smaller than 0.1 mm, a dimension which includes the bacteria), is brought back to the caecum, whilst the "solid" fraction containing the coarse particles (larger than 0.3 mm), forms the hard faeces which are excreted out of the rabbit (Björnhag, 1972). In fact, thanks to this dual function the colon produces two different kinds of faeces: hard faeces and caecotrophs. Their chemical composition can be seen in table 4 below

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If the hard faeces are evacuated in the litter, conversely, the caecotrophs are recovered by the animal as soon as they are released from the anus. To this end, during the emission, during an overall grooming operation, (Faure et al, 1963) the rabbit turns around, sucks up the soft faeces as soon as they come out of the anus, then swallows them without chewing them. Therefore, the rabbit can, without any inconvenience, practice the recovery of caecotrophs even if it is on a wire mesh floor. This is why if a breeder observes cecotrophs under the cages of his rabbits, it means that the animals are disturbed. In case of accumulated litter under wire mesh cages, the hard droppings roll over each other when they reach the ground and thus form "spread" piles. If caecotrophs are not picked up by the animal due to a temporary or permanent stress, the mucus around them tends to "stick" the droppings to each other. In this case, the pile of droppings under the cages (directly below the hindquarters of a rabbit when it is consuming in the feeder) is then of "pointed" shape.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| When everything is functioning normally, large quantities of soft faeces can be found in the stomach, where they account for as much as three quarters of the content (Gidenne and Lebas, 1988). The caecotrophs are digested in exactly the same way as "normal" feed. Bearing in mind the eventually recycled fractions, once, twice, even 3 or 4 times, and depending on the type of feed, the digestive transit of the rabbit lasts about 15 to 30 hours (20 hours on average). The general functioning of the digestive tract is summarized in figure 17. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It is worth remembering that half of the caecotrophs content is made of bacterial bodies and the rest is constuted by partially degraded feed residues and by the remains of secretions from the digestive tract. The bacterial bodies are an important source of proteins of high biological value, together with hydro soluble vitamins. Caecotrophy practice, a priori, is of considerable nutritional value. In a healthy rabbit fed on a balanced diet, caecotrophy provides approximately 15 - 25 % of the daily protein intake and covers the total requirements of vitamins B and C . However, this type of functioning of the digestive tract and the quantities involved limit the quantitative impact on protein nutrition, on the contrary the contribution of caecotrophy to the hydro soluble vitamins supply is essential. The administration of vitamins is often advised, for example during the days following weaning, because of the possible risk of digestive disorders which stop the hydrodulublrd vitamins supply.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Figure 18 shows the influence of the amount of fibre ingested (fixed composition), on the feed retention time in the different segments of the digestive tract. It should be remembered that the effects on retention times in the stomach and small intestine tend to compensate each other but the differences between extreme feeds do not exceed 2 hours. On the other hand, a reduced supply of fibre has more effect on the time during which the bolus is retained in the caecum: between 9h 40 min. and 21 h 30 min if the lowest fibres quantity is taken in consideration | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Caecotrophy regulation depends on the integrity of the digestive microbiota as well as the ingestion rate. The ingestion of caecotrophs starts 8 - 12 hours after feeding in restricted animals or after the ingestion peak in animals fed ad libitum. The ingestion rate in animals fed ad libitum and consequently the caecotrophy rate, are the result of the light period to which they are subjected (see below Feeding behaviour). It should also be pointed out that caecotrophy depends on internal regulation mechanisms which are not completely known today . For example, adrenal gland ablation implies that the animal no longer practises caecotrophy; the administration of cortisone to adrenalectomized animals enables normal caecotrophy behaviour to be resumed. It therefore appears that digestive transit in rabbits is dependent on adrenalin secretions. Stress-related hypersecretion causes hypoperistalsis (which increased retention time , effect similar to the effect of a low fibre diet) and as a consequence promote a high risk of digestive disorders .

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Caecotrophy is observed in young kits (domestic or wild) around 3 weeks old, as soon as they start consuming solids in addition to the mother's milk. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Feeding behaviour has been studied mostly in rabbits fed a complete pelleted diets, or in studies on feed preferences using dry or fresh feeds (grains, straws, hay, roots, amongst others). However, various studies of rabbits in semi-freedom and wild rabbits provide a better understanding of the feeding behavior of domestic rabbits raised conventionally in cages or in parks. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ingestion rate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Suckling rabbits | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The first feeding of a young rabbit is very usually done during parturition itself. After parturition, the doe herself decides the suckling rate for her kits and she feeds them once a day (Cross, 1952). Suckling lasts 2-3 minutes and the female does not provide direct assistance to the young, she is content to position herself correctly above the litter to give good access to all the teats. Some does occasionally feed twice a day or visit the nest several times, leading "observers" to believe that lactation occurs 4-5 times a day. Multiple suckling is not interesting, as already demonstrated by Zarrow et al. (1965), when growth rate of kits fed by the mother once or twice a day were found to be identical to that of the kits fed during unrestricted visits to the nest.. These results were confirmed more recently for example by Tudela and Balmisse in 2003 who showed that if 2 feedings per day allow the young rabbits to obtain a greater volume of milk (+ 8%), but the total quantity of nutrients obtained is the same since the average weight of the young rabbits at 21 days is strictly identical in the 2 situations as had been previously demonstrated (Table 5).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sometimes, if the amount of milk is insufficient, the kits try to suckle every time the mother enters the nest, but she retains the milk. This behaviour is characteristic when milk production is insufficient. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Conversely, if the rabbits are offered to suckle twice a day at 12-hour intervals, but with a different mother, one in the morning and another in the evening, they readily accept. They can then ingest more milk (+ 37% on average, but ingestion is not x 2) and benefit from it for their growth (Table 6). It is therefore effectively the mother who determines the rhythm and the quantity of milk available to the young rabbits.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 6: Average

milk consumption and weight at 21 days of young rabbits sucking either

only their own mother in the morning,

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| During the third week of life, the kits begin to move in a perfectly coordinated manner. They ingest milk, a little drinking water, + a very small quantity of mother's feed if available, + some hard faeces deposed by the mother in the nest at their intention in order to provide an adult rabbit's mictobiota to her kits. During the fourth week, kits ingest more solid feed and water than milk. Changes in feeding behaviour at this period are truly extraordinary: the young rabbit under the mother passes from a single feeding per day to a multitude of solid and liquid meals more or less alternated and distributed irregularly throughout the day, rythm characteristic of the feeding behavior of the adult. It is also during of this 4th week of life that begins the practice of cecotrophy. In fact, in the stomachs of young rabbits sacrificed at 22 days, only milk and feed are found; while in young rabbits sacrificed at 28 days cecotrophs can be identified in the stomach in addition to feed and traces of milk (for details see the article of Orengo & Gidenne, 2005). The preferentially nocturnal ingestion of the solid feed is already marked. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It is interesting to note that when it begins to consume solid feed, the suckling rabbit has a clear preference for maternal feed even over feed which is better suited to its physiological needs. This suggests a role for the mother in learning to eat feed, but this has not been formally demonstrated. However, by playing on the appropriate flavoring of the "young rabbit" feed, it is possible to encourage them to consume more of it than maternal feed (table 7). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

feed intake by the young rabbits in a situation of free choice, the mother not having access to any of the 2 feeds. Source: Mousset, 2003. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Feeding behaviour of he weaned rabbit or of adult rabbit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| At the time of weaning, the young rabbits already have 30 to 40 solid or liquid meals per 24 hours (table 8). The total time spent on meals in a 24 hour cycle is, at 6 weeks, more than 3 hours. Then rapidly it drops to under 2 hours. If the rabbit is offered a non-pelleted feed (flour or mash), the time spent eating is doubled. Whatever the animals' age, feed containing over 70 % water (green roughage or roots, for example) at a temperature of 20 ºC, provides more than the required amount of water. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 8. Evolution

of the feeding behavior of male rabbits between 6 and 18 weeks,

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

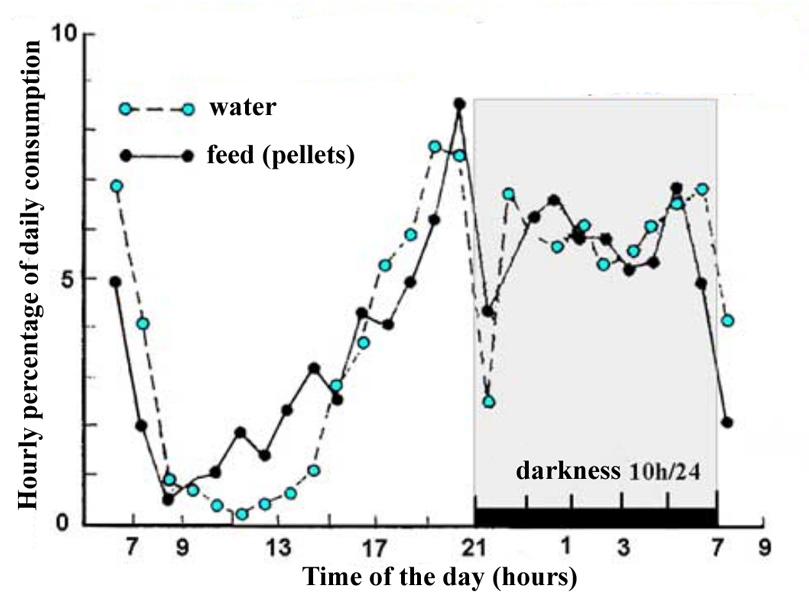

| The distribution of feed and water intakes is not homogenous during the 24 hours period (figure 19). The proportion of daily feed consumed on an hourly basis during the darkness period is greater than that ingested during the light period, for both solids and liquids. It should be pointed out that consumption is higher just before the lights are switched off in the raising room. In sub adult rabbits (3 kg New Zealand White) with 12 hours of light/24 h., nocturnal consumption represents almost two thirds of that observed in the total 24 hours cycle, due to increased feeding frequency but the amount of each meal is the same, 5-6 g per meal. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 19. Hourly distribution of wáter and pelleted feed consumption over a 24-hour cycle in a 12 week old rabbit. Source: Prud'hon et al (1975). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

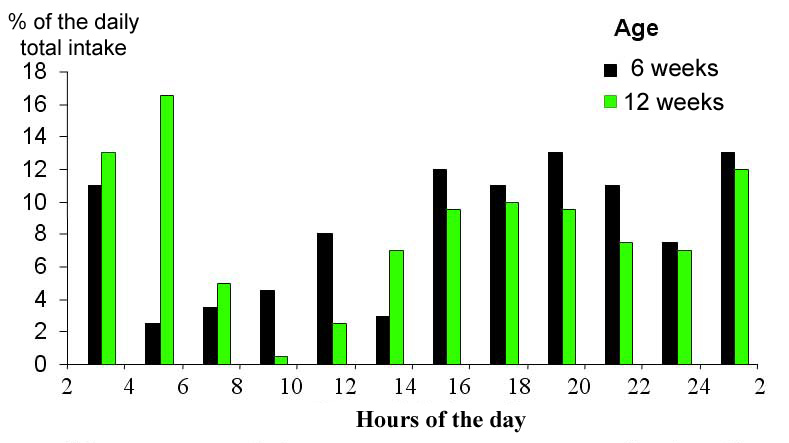

| As the rabbits grow, their nocturnal feeding behaviour increases. Feed intake decreases during the light period and the morning,"feeding rest" period between meals becomes longer (figure 20). The feeding behaviour of wild rabbits is even more nocturnal than that of domestic ones | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 20. Distribution of daily feed consumption in 2 hours increments, in 6 and 16 week old rabbits. Average consumption of 80 and 189 g of pelleted feed per day for the 2 ages. Lighting 12 hours a day from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. Source: Bellier et al. (1995). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Evolution of feed ingestion in terms of age and physiological status | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The amount of feed and water ingested depends firstly on the nature of the feed given to the rabbits at a given time, and especially on the digestible protein and energy content: high energy content tends to reduce consumption and high protein content tends to increase it . These amounts also depend on the type of animal, its age and breeding status or on the ambient temperature. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consumption of kits depends to a large extent on the animal's age, as well as other factors (figure 21). Using spontaneous consumption in adults as reference, (for example, 140-150 g DM/day, in New Zealand White rabbits weighing 4 kg), it was recorded that the daily consumption of a 4-week-old rabbit is one quarter, whilst its live weight corresponds to only 14 % of the adult's live weight. At 8 weeks the equivalent proportions are 62 and 42 % and at 16 weeks, 100 to 110 % and 87 %. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The rabbit regulates its ingestion according to its energy needs, like other mammals. Chemostatic mechanisms are involved, through the nervous system and blood metabolites linked to energy metabolism. However, in monogastric animals glycemia plays a key role in the regulation of feed intake, while in ruminants plasma concentration in volatile fatty acids plays an important role. Given that the rabbit is an herbivorous monogastric, glycemia seems to play a preponderant role in relation to the concentration of VFA, but the respective role of these two metabolites (glucose vs VFA) on the regulation of ingestion remains today poorly understood. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Voluntary ingestion is in fact proportional to metabolic body weight (PV0.75, and is approximately 900-1000 kJ ED / day / kg PV0.75 (ED: digestible energy). Chemostatic regulation would intervene beyond a DE concentration of 9 to 9.5 MJ / kg. Below this level, a physical type regulation prevails which would be linked to the state of fullness of the digestive tract. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The ingestion of caecotrophs increases up to 2 months of age and then remains stable (figure 22). Expressed in fresh matter, it evolves from 10 g/ d to 55 g/ day between 1 and 2 months of age, and represents 15 to 35% of feed intake. However, it is possible that these values are underestimated given the measurement technique used in this work (temporary installation of mini shackles preventing re-ingestion of caecotrophs). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spontaneous feed consumption in rabbit females varies during the reproduction cycle (figure 23). Decreased consumption at the end of gestation is marked in all does and in some cases, solid feed intake can stop altogether on the eve of parturition. In contrast, water intake never stops. After parturition, feed ingestion increases rapidly and can exceed 100 g of dry matter per kg of live weight. Water intake is also significantly increased at this time: 200 to 250 g/day per kg of live weight, i.e. up to one liter /day for a 4 kg rabbit doe. When a doe is simultaneouly gestating and lactating, her feed consumption is comparable to that of a only lactating doe, and never exceeds this amount. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ingestion of feed and water depending on the environment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Effect of temperature | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The amount of energy a rabbit uses up, depends on environmental temperatures. Feed intake compensates for this and therefore also depends on the environmental temperature. Laboratory work carried out shows that when temperatures increases from 5ºC up to 30º, the consumption of growing rabbits is reduced from 180 g down to 120 g/day for dry feed, and water ingestion is increased from 330 up to 390 g/day in the same conditions (table 9). A more precise analysis of behaviour shows that when the temperature increases, the number of meals / 24h. (solid and liquid) decreases . For example young New Zealand females go from 37 solid meals at 10º C down to 27 meals /day at 30º C. On the other hand, if the amount of feed consumed in each meal decreases as a result of high temperatures (5.7 g/meal at 10° C and 20° C compared to 4.4 g at 30° C), the opposite occurs for water , the amount consumed each time increases with the temperature increase (from 11.4 up to 16.2 g per meal, at 10 °C and 30 °C). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 9. Feeding behavior of growing rabbits as a function of the ambient temperature. Consumption and weight gain in g/ day. Source: Eberhart (1980). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

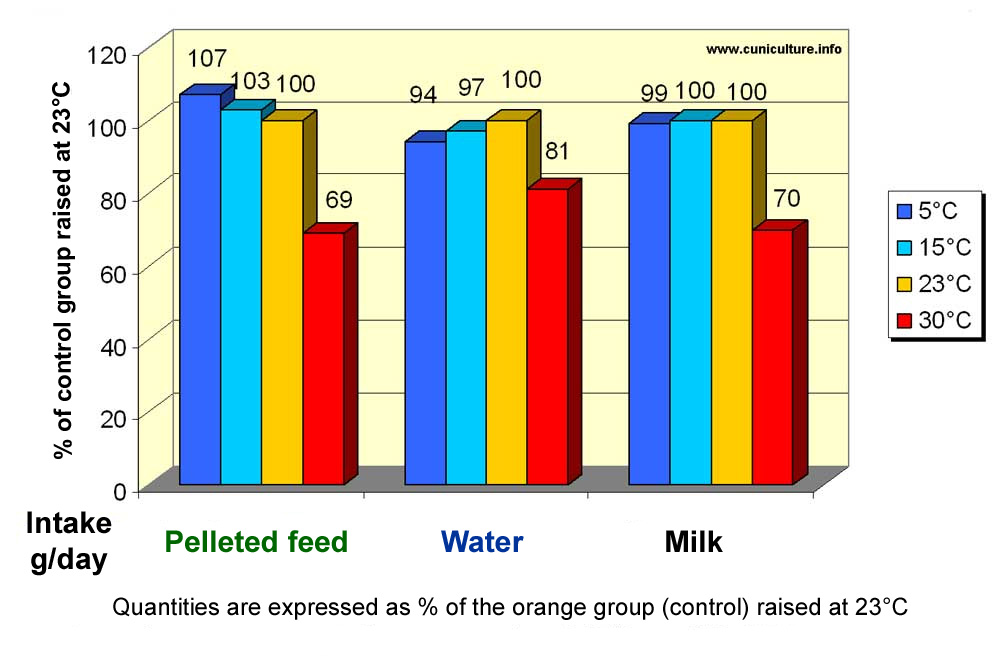

| If

the consumption of growing rabbits is affected at 30 °C and above

, that of breeding rabbits is equally affected as shown in figure 24.

It should be noted that milk production is also affected by heat in the

same proportion as the consumption of pelleted feed (at 30°C milk

production is 70% of the value measured at 23° C). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 24: Effect of ambient temperature on feed and water intakes, and on rabbit milk production. (Source: Szendrö et al., 1998) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A study carried out in Italy by Finzi et al. (1992), shows that if the temperature increases (tests carried out at 20 °C, 26 °C and 32 °C), the ingested feed/water ratio increases significantly, which is nothing new. However, the different ratios between ingestion and excretion also change (table 10). These authors propose using these ratios (the ones easiest to calculate locally), to verify the existence of thermal stress in rabbits. However, this suggestion should be validated before implementation. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ingestion and excretion in adult rabbits. Source: Finzi et al. (1992). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relation Water-Feed | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Effect of other environnmental factors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other environmental factors have also been studied in domestic rabbits, such as the lighting schedule or housing systems. In the absence of light (24 hour darkness), the ingestion of the growing rabbit is slightly increased in comparison with rabbits subjected to a light program with a 24 hour cycle. In the absence of light, the rabbit organizes its feeding program on a regular cycle of 23.5 to 23.8 hours, with 5 to 6 hours devoted to the ingestion of caecotrophs. In continuous lighting, the feeding program of the rabbit is organized on a cycle of approximately 25 hours, and the total feed intake / 24h is reduced and the growth performance too. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

According to Hungarian studies published in 2000, in the reproductive female, a modification of the lighting program, by introducing 2 periods of darkness of 4 hours, on cycles of 12h (light, darkness, 2 cycles/24h) reduces the ingestion and causes an increase in milk production, thus leading to better feed efficiency.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| As mentioned earlier, the type of cage also influences the feeding behavior of the rabbit. Ingestion is reduced if the density of rabbits in the cage rises, possibly due to greater competition between animals for access to the feeder, but also mainly due to reduced mobility of animals and therefore of their nutritional needs (table 11). This density effect is also observed for rabbits reared in individual cages (effect of cage dimension) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 11.

Feed consumption

and growth of rabbits between 32 and 68 days of age, at a density |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Feed restriction, feeding behaviour and digestive development | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It may be necessary to limit the amount of feed given to growing rabbits for several reasons. This is for example recommended in the event of epizootic rabbitenteropathy, the ERE named EEL in French (see for example the articles in French which were devoted to this topic in the magazine part of this Website in 2003 or in 2009 or the report of the round table devoted to it by the Association Scientifique Française de Cuniculture in 2007). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quantitative rerstriction | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| When a limited quantity of food is distributed to rabbits, the daily intake is consumed all the more quickly as the restriction is more marked. For example for rabbits housed in individual cages or in pairs, an allowance representing 85% of the pellets consumed ad libitum, is completely consumed in about 16 hours. If the allowance represents only 70% of the consumption ad libitum, it is completely consumed in just under 10 hours. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In the case of rabbits conventionally reared at a rate of 8 per cage, a pellets allocation of 85% is completely consumed in 8 hours (98% in 5 hours - figure 26) if only one rabbit can eat at a time (effect of competition) while if two rabbits can eat simultaneously, only 89% of the same allowance are eaten in 8 hours. For more details in French on the feeding behavior of quantitatively rationed rabbits, see the article Tudela and Lebas (2006) in the Magazine section of this Website. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regardless of the level of restriction, rabbits do not increase their instantaneous rate of ingestion. They increase the duration of each meal, in particular the one following the distribution, and reduce the interval between each meal. The duration of these meals is however limited by the stomach capacity which represents at most only about fifteen grams of pelleted feed for a 2 kg rabbit, knowing that the stomach of a rabbit is never empty before the start of a meal. This situation allows 8 rabbits to eat in turn, even in a feeder with only one eating station. For example, even a 60% restriction does not increase the variability in weight between the rabbits in a collective cage, which means that each of the 8 rabbits was indeed restricted at the same level and that none of them consumed the "neighbor's" share. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Restriction of access time to the feeder | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| At the end of the 1980s, the Hungarian team from Kaposvar under the direction of Zs. Szendrö carried out a systematic study of the amount of feed ingested by growing rabbits as a function of the time allowed for consumption over 24 hours (a duration per 24 hour cycle varying from ½ hour to 16 hours) in comparison with ad libitum fed rabbits (figure 27). So when rabbits have 8 hours a day to consume their ration, they consume about 80% of what rabbits fed ad libitum consume. More drastic reductions in access time result in an almost linear reduction in the quantity of feed consumed, which is reduced to 20% for an access time of only ½ hour/24h. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Restriction of access time to the waterer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Feed restriction and importance of the digestive tract | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| As a general rule, any rationing less than 80-85% also tends to reduce the growth rate of the animals. On the other hand, the digestive tract is significantly less affected by feed restriction than the body as a whole, as shown by the data in Table 14. Moreover, if a food restriction systematically promotes an increase in digestive content, the distribution of the latter between the different segments depends largely on the restriction mode selected. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 14 : Incidence of various modes of feed restriction on digestive development in rabbits slaughtered on average at 67 days. Source: Lebas and Laplace (1982). [Commercial complete pelleted feed containing 16.5% proteins and 14.0% crude fiber]. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

From

a practical standpoint, it should be remembered that any restriction,

reducing the growth rate, will also reduce the slaughter yield .

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Feed preferences in rabbits | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Feeding behavior of wild non-captive rabbits ("grazing" rabbits) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Feeding behavior of domestic rabbits in a free choice situation (rabbit in cage with a choice for their feed) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Some studies have shown that the rabbit can recognize basic flavors, such as salty, sweet, bitter, sour. He shows a preference for sweet flavors, and chooses for example a feed containing additional sugar or molasses rather than a food of the same composition containing no additional sweeter. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In captivity, the adult rabbit can sometimes express a "delicate" feeding behavior, with a momentary refusal of ingestion after a change of feed, or a systematic refusal of certain feeds. It is then observed a scratching behavior of the content of the feeder, whether the feed is in pelleted form or in flour. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Feeding rabbits on roughages + a complementary concentrated feed may cause problems if the roughage does not taste good. When rabbits are free to choose between concentrated energy feed and fibre (straw, for example), they are incapable of balancing the ingestion of both feeds and growth decreases. If producers find themself in this situation, they must limit the amount of concentrated feed, or the feed that the rabbits prefer. This is what happens in the case of certain green roughages of little nutritional value. As observed by Gidenne (1985), the situation is quite different if the rabbit is offered two concentrated energy feeds, such as complete pelleted feed and green bananas. The growth rate of the rabbits with free choice is similar to that of the control (only complete pellets), and the ingestion of digestible energy is identical to that observed with only pelleted feed. In any case between weaning (5 weeks) and the end of thel (12 weeks), the proportion of bananas consumed dropped from 40% down to 28% of the daily intake of dry matter. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||